I just returned from an intriguing conference on Mediterranean Europe(s): Images and Ideas of Europe from the Mediterranean Shores in Naples, Italy. There, I gave a talk on how European Union historiography could look in times of existential crisis. Before my talk, I was introduced and my chair also mentioned my upcoming book on a cultural history of metal in Europe.1 In fact, in the exact moment when my chair mentioned this book, I did not look at the audience; but the mentioning of a “cultural history of metal in Europe” caused some laughter, however, most of all it caused interest and paying attention to my speech.

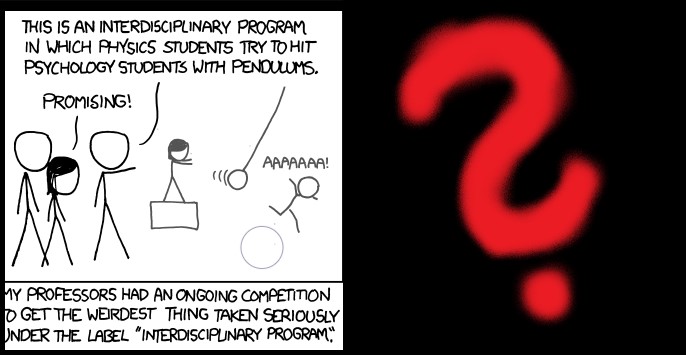

This is a situation, almost in a paradigmatic way, which I experience at practically every conference, lecture, course or other academic event outside of metal studies itself when my research on metal is mentioned. It causes a mixture of laughter, ignorance, however, predominantly it is a trigger of immediate attention. Here, the label “metal studies” becomes a signifier of novelty, interdisciplinarity but also of all stereotypes of metal culture. Hence, the question is how – strategically and proactively – metal studies should present itself to other academic discourses.

My “answer” also takes up an individual experience I had at the Naples conference. After the keynote on the event’s first day, I had an informal chat with the keynote speaker; she gave a really convincing lecture on theoretical issues of Mediterranean history, showing how personal stories and scientific historiography interact in historians’ individual careers and lives. After I gave her a short feedback, she told me that after hearing that I work in metal studies she had been asking herself: “Why does that guy research heavy metal?”

Again, here metal studies triggered immediate attention. However, this shows a fundamental lack of knowledge. I answered in a twofold way. First, I replied that most of all since about ten years metal studies has become a serious emerging field of research. So, I tried to give basic information. Second, I felt it was even more important to give a sense of how a European cultural history of metal is connected to the discourse discussed in Naples. In this respect, I anwered that – basically – a European cultural history of metal is part of a broad cultural history of Europe since the 1970s, of Europeanization, globalization and regional integration in the EU.

I mentioned two examples how metal history could give new insights: I told her that metal history in the 1980s was a cultural phenomenon in Europe, which crossed the Iron Curtain before 1989 – Iron Maiden toured Poland as early as 1984. I compared this phenomenon to other forms of culture such as cross-bloc-contacts in literature, academia or music. Like this, I tried to show how metal history was a form of subcultural European integration even before 1989.

Then, I told her about the development of extreme metal as a whole spectrum of subgenres since the 1980s. I mentioned that for a historian it is rather evident that extreme metal emerged in a decade which was the fin-de-siècle of an epoch which Eric Hobsbawm called the “Age of Extremes“.2 For me, there is a rather obvious, already linguistic connection between the emergence of extreme metal and the Age of Extremes. The latter is the context of the birth of new musical subgenres.

After this informal talk, the keynote speaker told me that this sounds highly interesting and she will look out for my book. One can intepret this as collegial practice of informal etiquette; yet this anecdote proves that metal studies causes interest. My idea is that to further nurture our field we ought to meet this interest strategically, proactively and respectfully. This means to provide basic knowledge about our field. Then, explaining the field’s aims and ambitions by describing cross-linkages to other discourses and giving empirical examples appears to be helpful.