The topic of a recent metal studies conference was ‘going to the country’, being focussed more precisely in the title’s second part ‘pastoral, national, musical’. 1 I am a contemporary historian who works in metal music studies; my aim is to write pieces of a scientific historiography of metal music as a ‘glocal’ subculture, giving it a scientific narrative.

When I reflect on the phrase of ‘going to the country’, my central thought is to narrate a history of ‘going to the country’ in metal. I ask myself: could this phrase be the ‘emplotment’ of at least a part of a cultural history of metal? My thesis is that, somewhat paradoxically, the phrase gives an answer to the question how musical, topical and aesthetical aspects of country music were integrated into metal culture. I argue that this processes between metal and country discourses, blending and hybridizing both, happened in a form of a historic emplotment, which Hayden White described as ‘satire’.2

l will go three steps to prove my thesis: as steps one and two, I discuss two empirical examples of recent metal culture, where country music was used in metal and hard rock music. By conceptually analysing both examples in a third section, I will try to show that this has the cultural-historical form of emplotment of ‘satire’, using irony in ‘going to the country’. This is an aspect of recent metal history’s development, being reflected in the emergence of an own academic discourse of metal music studies.

In these emerging debates, I introduced the term of ‘sonic knowledge’ to characterize the historian’s gaze on metal, which sees it as a historically shaped form of cultural knowledge in music. We can call this sonic knowledge.3

Steve ‘n’ Seagulls, ‘Farm Machine’ and ‘Brothers in Farms’

In 2015, the Finnish band Steve ‘n’ Seagulls (a pun on actor Steven Seagal) released their debut album ‘Farm Machine’.4 The group played classic heavy metal songs like Metallica’s ‘Nothing Else Matters’ and ‘Seek and Destroy’, or Iron Maiden’s ‘The Trooper’ and ‘Run to the Hills’, and hard rock classics such as AC/DC’s ‘Thunderstruck’ and ‘You Shook Me all Night Long’ on bluegrass instruments. They stripped the songs of their typical guitar-driven, distorted and heavy sound, and represented them as country music versions.

This redressing and reshaping of central musical and discursive elements of metal culture can be seen as acts of translation. The trope in which the final versions – bluegrass versions – appear is irony: playing originally heavy and aggressive tracks like ‘Seek and Destroy` or even Rammstein’s ‘Ich will’ in this style, prompts a caricature of metal culture and country culture. It creates a new space in which the stereotypes of metal (aggressiveness, anger, hyper-masculinity, satanism, etc.) as well as the cliché of country (farm life, rural styles of clothing, ‘primitiveness`, ‘backwardness’, etc.) are exposed as such constructions. This is the debut album’s cover:

Already this cover shows very clearly how the band sees ‘going to the country’: as a means of satire and irony; of satire of both – metal and country. This becomes even more obvious watching their Youtube clicks. Some of them went ‘viral’. Here is their version of Iron Maiden’s classic song ‘The Trooper’, which achieved no less than over 11 millions of views:

What is happening here? Being able musicians, they take a metal anthem, strip it of its core musical language of roaring guitars, speed and high-pitched vocals; instead of using this musical language of metal,5 Steve ‘n’ Seagulls redress the song, sonically, as a bluegrass song. Their habitual appearance, which is a quite awful cliché caricature of farm life, makes fun of both – metal and country. In this case, ‘going to the country’ means going to the country via the history of Metal. The form, in which this cultural-historical detour is gone, is irony and satire. This going-to-the-country-as-detour also was the case on the band’s second album ‘Brothers in Farms’ from 2016.6

Behemoth, Me and that Man and ‘Songs of Love and Death’

Let me analyze a second empirical example. In 2017, Adam Michal ‘Nergal’ Darski, singer and creative head of the Polish extreme metal group Behemoth, released a country-inspired album called ‘Songs of Love and Death’.7 In this musical project, Darski joined forces with British rock artist John Porter. Working together on dark country and folk-inspired, more or less acoustic guitar music, they called the project Me and that Man. Evidently, Nergal called himself ‘me’ whereas Porter was referred to as ‘that man’. Hence, this implies that Nergal is to be seen as the project’s actual protagonist, as the duo’s ‘self’ and ‘me’.

In this respect, forming a project which plays dark folk and country music, at the same time being the leader of a Polish extreme, black and death metal group whose latest album (‘The Satanist’ from 2014)8 was widely received as a seminal one, maybe even a future genre classic, becomes a remarkable symbolic act in discourse.

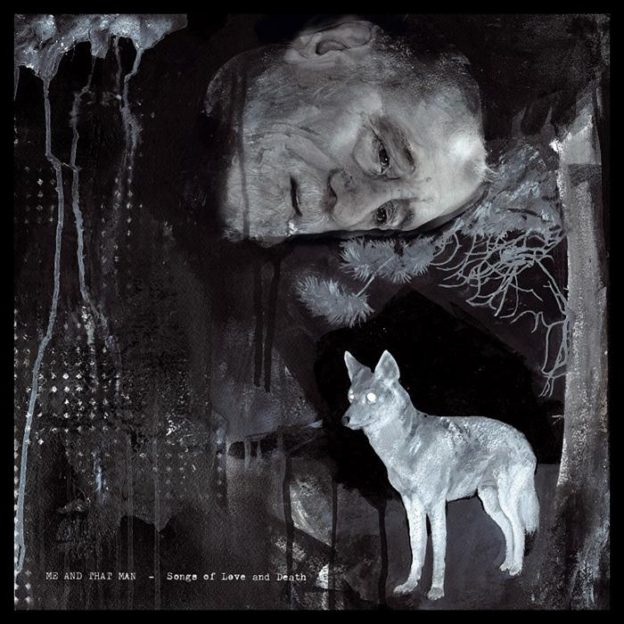

Nergal escapes his discourse of origin, which is extreme metal, and ‘goes to the country’. However, he does so by joining forces with an artist from the new field but at the same time sticks to his used dark lyrical and aesthetic contents. Somehow, one can see the album of ‘Songs of Love and Death’ as a reciprocal case of Steve ‘n’ Seagulls: Nergal used an optical travesty of metal themes to translate their core narrative of darkness to country. This is the album’s cover:

The cover’s contents embody the project’s artistic mode of operation. It shows an old man and a wolf. So, most of all the project works allegorically. It is a metaphor-in-music of metal culture, translated to country culture. This is its mode of ‘going to the country’. It becomes especially obvious in the clip to the song ‘My Church is Black’, featured on the album:

In the setting of a red-light strip club, it shows pictures of striptease, physical abuse, darkness, being bracketed together by a short storyline. Optically, this clip is quite easily to identify as metal, yet acoustically it renains country and folk.

Cultural-historically, in its discursive mode of operation, ‘Songs of Love and Death’, being released just a year ago, builds a very interesting example of ‘going to the country’. It imports, via imaginary and allegorisms, metal culture to country culture. It substitutes country images (which in the case of ‘Farm Machine` and ‘Brothers in Farms’ was obvious humour and irony, in the shape of kitsch and cliché) with metal images. However serious this meant darkness does appear, its mode of operation is the same – satire and irony. The discursive and cultural emplotment modes in irony and satire are, amongst others, parody, juxtaposition, comparison, analogy, and double entendre.9

All these techniques of emplotment use the vice-versa-substitution of supposedly paradoxical elements as their key mode of storytelling: in parody, exaggerated protagonists or storylines substitute the original ones; in juxtaposition, reciprocal substitution of antithetic elements is obvious; in comparison or analogy, the substitutional similarity of different narratives is the core; finally, in double entendre, different meanings are played with and can be substituted with each other. Thus, the supposed seriousness of the country culture in ‘Me and that Man’ is satire, too. How can we use these findings for a cultural history of metal – and popular music at large?

Sonic knowledge: ‘Going to the country’ as irony and satire in the emplotment of metal history

As historian, I ask myself: how can these two examples of ‘going to the country’, standing for a broader trend of looking for connections to other cultures of poplar music in metal history, be interpreted? How are they to be interpreted using the historian’s gaze in metal music studies?

My hypothesis is we can only historically meaningfully do so by applying Hayden White’s narratology on metal history. In his groundbreaking book ‘Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-century Europe’, the author showed that basically all scientific historiography is narrative and narratological construction, too. ‘Emplotment’, White’s key term, was defined as:

Providing the ‘meaning’ of a story by identifying the kind of story that has been told is called explanation by emplotment. (…) Emplotment is the way by which a sequence of event fashioned into a story is gradually revealed to be a story of particular kind.10

Reading this quote, we do not have to descend into the depts and apocryphes of the philosophy of history. Historians themselves barely dare do to theory. But it tells us that in history, and thus also in metal history, we ought to ask how a particular narrative is constructed. We ought to ask for its mode of emplotment: in its musical language, its lyrics, its imaginaries etc. Doing so for the case of ‘going to the country’ in recent metal history, we see that the core mode of emplotment is satire and irony. In recent metal culture, ‘going to the country’ means to use irony and metaphor as deconstructive ways of storytelling to give an epistemological travesty of both: metal and country.

And, finally, this gives us a clue on how to better historically understand metal (and maybe other discourses of popular music) in their historic dynamics. Basically, emplotment and narratives, as introduced by White, are notions of knowledge. Telling a history, fashioning events into a narrative, is a way of gaining and presenting historic knowledge. This could be a historical agenda, applying the historian’s gaze on metal music: seeing it as sonic knowledge which is constructed in certain historical spaces at a certain historical time. This is what historians of metal can meaningfully ask and aim for.

Conference ‘Going To The Country: Pastoral-National-Musical’, 8 to 11 March 2018, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee; http://iaspm-us.net/2018-iaspm-us-conference/, accessed 23/06/2018. ↩

H. White, Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-century Europe, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973; idem, The Content of the Form: Narrative Discourse and Historical Representation. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987. ↩

P. Pichler, ‘Homo ludens metallicus? On Huizinga, the historian’s gaze and sonic knowledge in Metal Music Studies’, in Stahl, 26.02.2018. Online, Url: http://www.peter-pichler-stahl.at/artikel/homo-ludens-metallicus-on-huizinga-cultural-history-and-sonic-knowledge-in-metal-music-studies/, accessed 06/03/2018. ↩

Steve ‘n’ Seagulls, Farm Machine, released 08/05/2015 on Spinefarm Records. ↩

D. Elflein, Schwermetallanalysen. Die musikalische Sprache des Heavy Metal, Bielefeld: Transcript, 2010. ↩

Steve ‘n’ Seagulls, Brothers in Farms, released 09/09/2016 on Spinefarm Records. ↩

Me and that Man, Songs of Love Death, released 24/03/2017 on Cooking Vinyl Records. ↩

Behemoth, The Satanist, released 03/02/2014 on Nuclear Blast Records. ↩

White, Metahistory; more broadly see B. Connery and K. Combe (eds.), Theorizing Satire: Essays in Literary Criticism, New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 1995; M. A. Seidel, The Satiric Inheritance: From Rabelais to Sterne, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1979. ↩

White, Metahistory, 7. ↩