This blogpost has a rather peculiar title – what is a “scientific concert review”? Isn’t a review a genre of text, a piece which treats concerts normatively, depending on their quality? What I want to try here is something else. Last Saturday, 20th January 2018, I visited the Vienna club gig of Polish Black Metal outfit Batushka, supported by the Swiss band Schammasch and Swedish project Trepaneringsritualen. I visited this gig as a fan, my “fan-review” can be read here.

But also I attented this concert at “Szene Wien” as a cultural historian, a scientist who does research in Metal Music Studies. And there was a lot of scientific material to see, experience and think about. Thus, what I want to do here is an experiment: I want to write an essay which uses the methods of the New Cultural History and recent research in Sound History to explain, or at least to take a look at a concert experience as scientific cultural-historical material.1 What I saw, smelled, felt, experienced at Szene Wien was not only leisure fun but also a form of historiographic and ethnologic empiricism.

In this essay, something like a first trial balloon on my blog, I want to approach the culture of Black Metal from an integral perspective; a perspective which takes the feelings of scientific concert visitors not only as immediate emotions but also as a form of cultural practice which is open to discursive meta-analysis. So – maybe and hopefully – this essay can give some fruitful insights to the cultural-historical implications of this gig. Indeed, there was an immense potential of history and historic discursiveness to think of.

As mentioned, last saturday Batushka, a Black Metal band from Poland, played, as part of their “European Pilgrimage” tour, a concert at Vienna’s Szene club. The band had Swiss group Schammasch, also a Black Metal project, and Swedish artist Trepaneringsritualen as their guests and support. I will start my analysis as a historian in chronological order, looking at the historical implications and contents experienced, listened to and seen, individually for each of the three artists/projects.

Trepaneringsritualen is an – at the first glance – obscure project from Gothenburg, Sweden. Soloartist Thomas Martin Ekelund claims to make “ritual music”. What he does on stage is a mixture of Black Metal screaming, performance and ambient music. Being the opener of the event, Eklund did a concert/perfomance of about twenty minutes during which he first covered his head and face with a hood, which he later removed. This is a photograph of his perfomance:

At a first glance, there is barely something historical about this show. But, taking a closer look, things change dramatically and give a lot of data for historical analysis. The key is the project’s name: Trepaneringsritualen. “Trepanation” is the still common notion, in medical and also historical discourses, which describes processes in which a human head is (forcefully) opened, using a drill, a knife, a saw or other devices.3 Practices of trepanation, having ritualistic, cultural and/or medical purposes and contexts, can be traced back to 12.000 BC.

Since the late 19th century, evidence discovered in shape of skulls show a vast history of trepanation around the globe. Such practices are often believed to have had ritualistic, cultural or religous characteristics (like metaphorically giving demons the opportunity to leave a head or get into it), but also medical contexts of healing. Too, many persons who underwent such processes survived, with their heads and skulls showing traces of healing.

So, from the point of view of scientific cultural history, what does Trepaneringsritualen do? He performs a solo show of Black Metal or ritual music for which he uses the ancient discursive code or notion of opening heads. By doing so, he performs a very drastic act: One could interpret Eklund’s performance as a process which metaphorically opens his, his audience’s or today’s men’s heads. And he does so, so to speak, via a deep historical practice. In Trepaneringsritualen, history has the role and function of using the past to invade and examine, quasi-culturally and quasi-medically, our current thinking and culture of the 21st century.

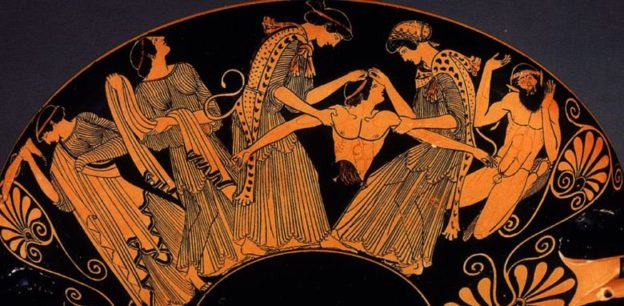

After Eklund, Swiss act Schammasch took the stage. This band’s performance was quite another experience. The group used three electric guitars, bass, drums and some additional drums played by their singer/guitar player. They used items like a goat head and the evaporation of thick fog on stage, and close to the stage, to create an atmosphere of ritualism, darkness and trance:

Music- and sound-wise, this performance was much heavier, thicker and doomier than the previous one. Consciously, the artists used a climax of slower and then growingly faster and rawer songs to create this experience. The historicism inherent of their concert used the imaginaries and symbols of religion, predominantly of medieval Catholic tradition. The clothes worn by the artists (as shown for example in the photograph above) reminds us of monasteries, of medieval monks. Too, the hoods covered the faces and anonymized the band, which made their figures even more allegoric in their historicism.

I think it is not exaggerated to state that Schammasch’s stage acting contained and harked back to medieval figures like Saint Francis of Assisi. Combining this dresscode with items like a goat head, gave history a special role: in the anonymizing and conservative as well as metaphorical allegorism of monk’s clothes, it served to construct a juxtaposition of the Middle Ages and the postmodern sound of Black Metal. In this case, history was the optical design of Black Metal, triggering ritualism, darkness and maybe fear.

Finally Batushka got to play their set. This was the second time I saw the group playing their entire “Litourgiya”-album. On this record, their debut, the group used elements of Orthodox liturgies (chants etc.), and combined it with Black and Doom Metal to criticize this discourse of religion. This is a photograph from the concert:

History (and its present) cannot be used more explicitly than in Batushka’s stage show. Most of all their singer, wearing a robe ressembling of a priest (but also having the notorious Third-Reich-“SS”-skull printed on the hood), used a very strict and monotonous mode of stage acting (for example shown in the photograph above). The whole show can be read as an “Orthodox Black mass” which used the rich history of the Divine Liturgy since the fourth century AD.6 In this performance, history gets broken up and becomes a tool of critique and parodistic irony.

What can we learn from this? First, history is immensely present in the discourse of Black Metal, at least in these bands’ discourses. Second, we can see the attending of a concert not only as a pure and innocent leisure activity but also as a way of collecting empirical, cultural-historical data. Material which is beforehand seen, heard, smelled and felt, but is open to scientific enquiry and meta-analysis.

See Peter Burke, What is cultural history? Polity Press: Cambridge 2008; and on the recent discourse of sound history see Horst Schulze (ed.), Sound Studies: Traditionen – Methoden – Desiderate. Eine Einführung, Transcript: Bielefeld 2008. ↩

Photograph of Trepaneringsritualen, Szene Wien, 20.01.2018, copyright: Corinna Doppelhofer. ↩

See Robert Arnott e.a. (eds.), Trepanation. Discovery, history, theory, Swets & Zeitlinger: Lisse e.a. 2003. ↩

Photograph of Schammasch, Szene Wien, 20.01.2018, copyright: Corinna Doppelhofer. ↩

Photograph of Batushka, Szene Wien, 20.01.2018, copyright: Corinna Doppelhofer. ↩

See Robert F. Taft, The Byzantine rite: a short history, Collegeville, Minn. : Liturgical Press, 1992. ↩