Nine days ago, on the day of the ‘Brexit’-votum in Great Britain, I took part in a scientific conference dealing with the ‘notorious’ topic of “European Solidarity”: there, we discussed the question wether European solidarity is to be seen, historically, as ‘the bonds that unite’ Europe. Doing so, on the day of the success of the ‘Leave’-campaign in Great Britain, made me feel a bit like being trapped in a mental state of British black humour – we discussed European solidarity while one of the biggest EU member countries voted to turn its back on European solidayrity.

This was not only a case of cultural cynism but of an overall trend in global and EU political discourse where emotional arguments and strategies had been successfully employed to reach certain nationalist and authoritarian political aims. The ‘Leave’-campaign used the fears of a split society (‘older vs. younger’; ‘educated vs. less educated’; ‘rural vs. urban’; ‘poor vs. “rich’) to pursue its nationalist and populist agenda. To vote “Leave” in Britain on 24th June, had its politico-cultural counterpart in the success in elections of Austria’s FPÖ, of France’s Front national, of the AfD in Germany, etc. All these “movements” and their discourses clinge to a global trend of leaving behind ‘Western’ liberalism and its culture of pluralism and anti-authoritanism. In fact, theses discourses and their anti-European stance of political speech are the form authoritanism takes in the middle of 2016.

However, this is not the authoritanism we know from theinterwar-period of the 1920s and 1930s. It is a new kind of authoritarian discourse which stems from a lack of visibility of meaning and representation in the global post-1989 world; most of all since the ‘Digital Revolution’ made the ‘Global village’, predicted by Marshall McLuhan, had become reality. We live under the auspices of a permanent cultural stress and tension, a digital fog of information which makes our identities become blurred, when there seems to be lrgz no boundaries of space and time. In this cultural condition, solidarity – European solidarity – has become an almost impossible norm: Whom in Europe (or our local and regional neighbourhood) should we feel solidarity for if societies and groups of the USA, of Asia, of Africa and other parts of the world seem, in the digital context, to be much closer, or, at least, as close as Europeans themselves? This lack of the visibility of cultural solidarity in Europe, because of our today’s world cultural structures, is the root of the new authoritanism: its discourse of nationalism and protectionism seems to create a sphere where solidarity remains alive – yet, this is an illusion.

Hence, in 2016 and beyond, we need new cultural discourses enabling us to build bonds of solidarity in Europe and the European Union, in a digitally and economically, and socially globalized world. We need to find new elements of community, cultural artefacts of solidarity that remain visible even if Chinese and Japanese, or Brasilian and American people seem to be much closer to our lives in popular culture than our European neighbours. This has to be a new kind of ‘imagined community’.1 We have to find a new kind of collective imagination of our European identity and ‘European soul’ that matches this new cultural condition.2

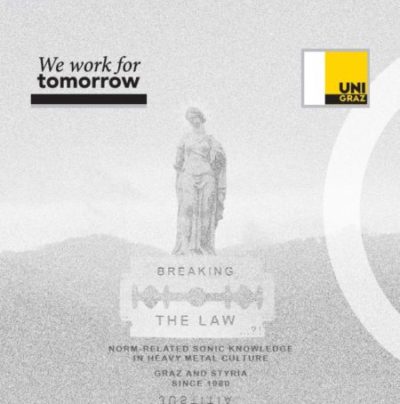

This is where the global imagined community of Metal Music, as a global discourse of popular culture, economy and leisure comes in. In the global Metal Music community there is a kind of solidarity that remains alive in times of globalization and its phenomena of the dissapearing of boundaries of spatial and temporal imagination. Actually, just because of the fact that today, in a world of global-wide communication where the solidarity of the Metal Music community can be established in a timeframe of seconds (and where local contexts depend from its overall global level of imagination), this imagined community found its structure as a growing and established field of cultural practice.3

That Metal Music has progressed to mainstream and has become a global and European subject of an own branch of scientific discourse, Metal Music Studies, forms this development’s climax; it means that in Metal Music solidarity of all ‘Metalheads’ around the world can be imagined because global cultural infrastructure of communication and information have formed a tool-like discourse of collective imagination which allowed this development to become historical reality.4 In a nutshell, Metal Music discourse made appear a global community of solidarity whose identy stems from its ability to remain visible in our times of globalized blur of cultural realities of belonging.

Hence, what we have to ask for is, how this remains possible in times of crisis, looking for a structure of cultural discourse in Metal Music which we could learn from something for European integration history. The answer to this question lies in the fact that Metal Music discource has become a field of social practice in which the global framework of the identy of being a ‘Metalhead’ and their local roots of belonging form a liquid and hybrid form of coherence.5 It creates solidartiy because globalization and localization work in parallel tracks, they build on synergies. Here, solidarity is a form of coherence in which an African ‘Metalhead’ feels solidarity for American and European fellow-fans of Metal Music and, at once, remain attached to his regional and local cultural.6 This form of coherence is to be sought for in discourses of European solidarity. In a nutshell, agents of European solidarity coult take a glimpse at and learn its lesson lesson from the establishment of the solidarity in Metal Music and its global way of collective imagination. Maybe, as Europeans and EU Europeans, we should look for the Metalhead woven into our collective European soul.

cf. Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso 2006. ↩

For a recent narrative on this, cf. Pichler, Peter. 2016. EUropa. Was die Europäischen Union ist, was sie nicht ist und was sie einmal werden könnte. Graz: Leykam. ↩

Cf. Deena Weinstein. 2015. Rock’n America. A Social and Cultural History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press;and Andy R. Brown e.a, eds. 2016. Global Metal Music and Culture: Current Directions in Metal Studies. London: Routledge. ↩

cf. ibid. ↩

cf. ibid. ↩

Cf. ibid. ↩