In my last post, I tried to use the methodology of Clifford Geertz’ anthropological ‘thick description’ to deal with the historical experience of a cultural historian at an Extreme Metal festival, linking regional history and conservative as well as Extreme Metal culture. In this post, I want to go a step further: I want to reflect upon how historical experience is constructed, seen, spoken, written and – finally – experienced, thought and felt of, in our age of digital cultures.1

To do so, I will analyse the historical experience I had when visiting the medieval castle of Ruine Gösting2 and listening to Black Metal music during my visit there. It was an experience thas has to be linked with current culture of historiography, Metal Music Studies and Metal music itself at once. It combined two spheres of historical experience: (1) Black Metal music as a discourse and field of contemporary culture of art, music and imaginary, and, (2) the material remains of a medieval castle as stimuli of historical experience; a field of material objects, over nine hundred years old.

The context

For it was a sunny and warm day in Graz, Austria, on 2. September 2016, I decided to take a short hike to the medieval castle of Ruine Gösting.3 The castle (its remains) is a well-frequented point of sigthseeing and hiking, located in the Northeast of Graz. It can be approached by a short hike of about half an hour from the city district of Gösting. The castle, or what is left of it today, was mentioned in local and regional historical sources for the first time in 1042.4

In the late Middle Ages, until the early modern period, the castle was an important fortress and ‘checkpoint’ in the Northeast of the city of Graz. Its location on a hill, situated about two hundred meters higher than the city itself, enabled then Stytrians to control and protect this area.5 Hence, the castle was an important building and institution of regional defense, control, organization, administration, and, therefore, culture.6

Being used as the city’s gun powder storage until 1723, the castle was an important point and aspect of regional and local culture and narratives.7 Having its own history – material history of culture – since at least 1042, the remains of Ruine Gösting are a field of intense historical experience. For any visitors, its thick walls, towers, little caverns and ‘dungeons’, provoke feelings and thoughts which hint at its past. In fact, provoking feelings of visiting a place that was important in history, representing the past of Graz and Styria, makes the place nothing else than a material source of history. Yet, any experience of history via this source remains constructive and discursvively produced.8

Listening to Black Metal as historical experience

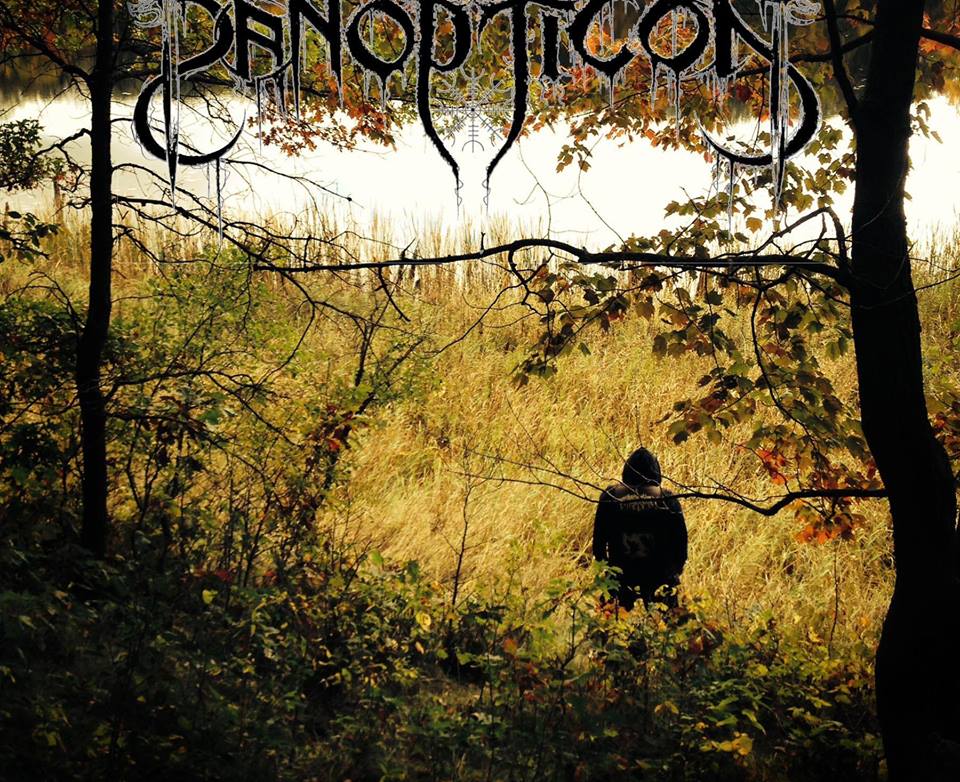

As I approached the castle, its remains lying on the top of the Göstinger Ruinenberg, I was listening to Black Metal music, using in-ear headphones. I decided to do so, because I felt – and thought – that listening to current Black Metal music, released in 2016, would produce a good ‘soundtrack’ or ‘auditive context’ when hiking up to the castle. I decided to listen to American Post Black Metal project Panopticon’s9 2016 release Revisions Of The Past.10

Panopticon is a one-man Extreme Metal project, hailing from Louisville, Kentucky, USA.11 The band is, in a certain way, an exceptional project in Black Metal music. It promotes ‘left’ political ideas of criticism and ideologies in music; it is not the only artistic groupto do so in Black Metal but many ‘orthodox’ or ‘traditional’ Black Metal bands choose to be ‘apolitical’ or to promote ideologies of anarchism, nihilism, satanism, destruction and other ‘blackisms’. Panopticon’s name comes from the metaphor of the cultural concept of the same name which Michel Foucault, in his path-breaking works of the 1960’s, stated to be the epitome of modern cultural history since the early modern period, of ‘governmentality’.12

I do not know exactly why I decided to specifically listen to Panopticon when approaching the castle of Ruine Gösting. But, and that being the decisive aspect, listening to Revisions Of The Past, in my thoughts and feeling, being open to later cognitive introspection, provoked an imaginary similar to, even matching the atmosphere of the historical source of the castle. Ancient castles, woods, knights, sorcerers, dungeons, monsters and so on, certainly are well-established stereotypes and clichés, even kitsch in Metal music. So, we have to see the connection between the imginary of current Black Metal discourse and material historical sources, as a field of historical experience, critically, in the mode of cultural deconstruction.13 A good way to do so, is to compare the visual imaginary Revisions Of The Past bears (most of all, its cover), the band’s overall imaginary as a ‘one-man-group’, and the images I took at Ruine Gösting:

Comparing these images, (1) the cover of an Exreme Metal album from 2016, the self-presentation of the artist, and (2) fotographs of the remains of a medieval castle, we can conclude that both form one historical portfolio of images, tropologies and semantics. Both fields of imaginaries represent history in the same way: the deal with forests, mysticism, old and ‘secret’ buildings; their mood and atmosphere is darkness, mysticism and getting away from today, disappearing into history, a sort of escapism. In a nutshell: in the empirical examples of Panopticon’s Revisions Of The Past and the castle of Ruine Gösting, the present and the past are not divided but form one semantic network of representations.

This is a rather suprising finding: it means that in this empirical case of Black Metal and conservative, ‘mainstream’ material culture of historical sightseeing, the imaginary of temporality is the same. When asking how the past is experienced in both cases, the Extreme Metal culture of Panopticon’s album and visiting Ruine Gösting, the answer leads to the same semantic network; that means, in current culture, also in this case, Extreme Metal music is not apart of society or mainstream historical culture but an integral part of it. So, what can we conclude from this for Metal Music Studies?

The epistemic apriori of the cultural history of Metal Music

When taking into account the experience I had on my hike to Ruine Gösting, seeing it retrospectively, using the method of introspection20 to deal with it self-reflexively, we see that – at least concerning these empirical examples – current historical experience (Black Metal music by Panopticon) and traditional material sources of history (the remains of Ruine Gösting) are not to be seen as divided (i.e. as contemporary and past culture) but as one historical network and discourse of meaning.

The present flows into the past, and, vice versa, the past flows into the present – both depend on each other, construct a liquid discourse. The conclusion from this argument needs further theoretical and empirical work of research but, at this point, it seems to be essential: we have to think of the cultural history of Metal music as a strictly ‘presentist’ phenomenon. Experiencing the past in Metal Music (Studies) means to describe the past as a shape of the present. This is a strong logical claim; but, too, an apt starting point for further theoretical and historical research in Metal Music Studies.

The last broad discussion concerning historical experience evolved around Frank Ankersmits book ‘Sublime Historical Experience; cf. Frank R. Ankesmit: Sublime Historical Experience. Stanford/Cambridge 2005; on the debate, cf. Peter Icke: Frank Ankersmit’s Lost Historical Cause: A Journey from Language to Experience. London 2011. ↩

Cf. https://www.graztourismus.at/de/sehen-und-erleben/sightseeing/sehenswuerdigkeiten/burgruine+g%C3%B6sting_sh-1204, retrieved 07.09.2016 ↩

Cf. ibid. ↩

For the history of the castle, cf. Robert Baravalle: Burgen und Schlösser der Steiermark. Eine enzyklopädische Sammlung der steirischen Wehrbauten und Liegenschaften, die mit den verschiedensten Privilegien ausgestattet waren. Mit 100 Darstellungen nach Vischer aus dem „Schlösserbuch“ von 1681. Graz 1995, pp. 9-13. ↩

Cf. ibid. ↩

Cf. ibid. ↩

Cf. ibid. ↩

Cf. Achim Landwehr: Historische Diskursanalyse. Frankfurt/Main 2008. ↩

Cf. https://www.facebook.com/TheTruePanopticon/?fref=ts, retrieved 07.09.2016. ↩

For a review in German language and information, cf. http://www.metal.de/reviews/panopticon-revisions-of-the-past-185985/, retrieved 07.09.2016. ↩

Cf. https://www.facebook.com/TheTruePanopticon/?fref=ts, retrieved 07.09.2016. ↩

Cf. Michel Foucault: Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York 1977; also, cf. idem: Security, Territory, Population. New York 2007; and, idem: The Birth of Biopolitics. New York 2008; broader, reflecting upon the origins of the metaphor in Jeremy Benthams thought, cf. Janet Semple: Bentham’s Prison. A Study of the Panopticon Penitentiary. Oxford 1993. ↩

Cf. Landwehr, Diskursanalyse. ↩

Cover of Panopticon, Revions Of The Past, 2016; source: https://nordvis.bandcamp.com/album/revisions-of-the-past, retrieved 07.09.2016. ↩

Picture of Panopticon as ‘one-man-group’; source: https://www.facebook.com/TheTruePanopticon/photos/a.157273827626137.28743.118131858207001/634967606523421/?type=3&theater, retrieved 07.09.2016. ↩

The way up to Ruine Gösting; picture by Peter Pichler. ↩

Approaching Ruine Gösting; picture by Peter Pichler. ↩

Approaching Ruine Gösting; picture by Peter Pichler. ↩

Inside Ruine Gösting; picture by Peter Pichler. ↩

Cf. Timothy Wilson: Strangers to Ourselves: Discovering the Adaptive Unconscious. Cambridge 2002. ↩