Over the last two days, I had the wonderful opportunity of taking part in the inspiring Hardwired VII conference at the University of Salzburg. Already the seventh conference in this series, it was an event of intense discussions on topics of transdisciplinarity and transgression in metal studies. As such a stimulating event, it was an oportunity of further developing the scientific community in the field.

In this post, I want to reflect upon what – probably – can be called the ‘heart of metal studies’. Intentionally, I use this notion of the ‘heart’, because as a metaphor it evokes associations of vitality, life, energy and of the identity of the metal studies community. Worth remembering, German metal veterans Accept released a classic album called Metal Heart in 1985.1

Now what is at the heart of our field? From my point of view, taken together the two keynote lectures of the conference, by Rosemary Lucy Hill and Keith Kahn-Harris, summed up the crucial challenges scholars have to master in the coming years. Of course, I cannot deliver a full solution to the central problems of metal research in this blog post. From the perspective of a cultural historian, I want to comment upon the paradox at the heart of metal research.

In her lecture ‘”You’re asking the Wrong Question!” Methodology, Standpoint and Fandon in Metal Research’, Hill delivered an excellent analysis of the main problem of the field in its ‘teenage years’. Metal research is dominantly conducted by scholars, who also take part in the culture as metalheads. With this comes an obvious, structural conflict between the obligation of the scholars in us to keep a distant and critical view on metal and the metal fans in us, who love the music. Hill encouraged scholars to keep asking hard questions on the difficult aspects of metal, e.g. sexual violence, fascim, racism and misogyny.

In his keynote ‘Too much Transgression – Metal in an Age of Explicit Knowledge’, Kahn-Harris took up his work on metal culture and the concept of ‘reflexive anti-reflexivety’. For Kahn-Harris, today’s metal culture is to be seen as a culture in an age of abundant knowledge. Transgression takes new forms. He called these forms ‘transgressive literalism’, ‘transgressive unintellegibility’ and ‘transgressive inversion’. Also in his view, conflicts between stances to problematic aspects of metal have to be reconsidered.

For a cultural historian, both lectures thematize a paradox, which seems to form something like the heart, perhaps the dark heart of the field. This heart pumps into the field (and its community) its vitality and is its key problem at the same time. The core issue seems to be to develop theories, strategies and a communal habitus or ‘thought style’, which enable us of coping with the tensions between our identities as scholars and identites as fans in a productive way.

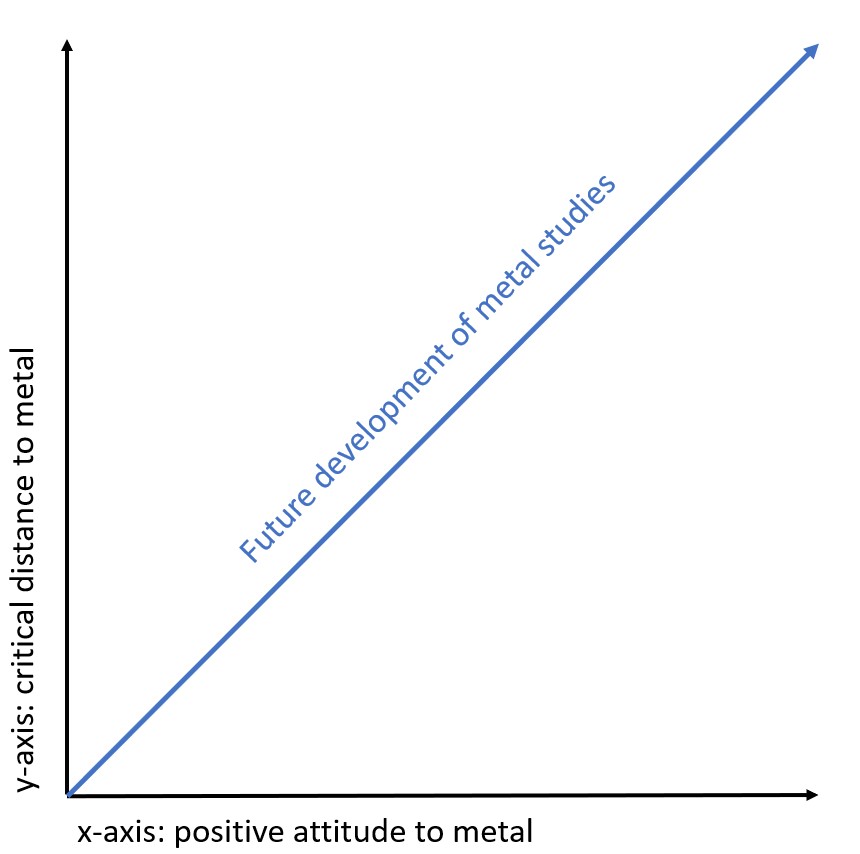

Logically, this is a classic paradox. The point here is, cultural-historical experience teaches us that usually paradoxes cannot be solved.2 In the long term, the identitary tensions that arise from such conflicts are solved only contigently by creating new spaces of knowledge, in that scholarship goes as far as possible in both directions: in the direction of critique and the direction of keeping a positive attitude to the culture. In a perfect metal studies world, which never will become reality, this could look a bit like this figure:

Thus, metal studies should not aim at defining a methodology or theory of metal that resolves the paradox. It should aim at constituting a new sphere of knowledge, in that we can go as far as possible into both directions. What Kahn-Harris called ‘engaged scholarship’ comes pretty close to this. With Hill, we should keep asking difficult questions. In this, history with its focus on longue durée developments over decades since 1970 could become an exciting enrichment.3

Accept, Metal Heart, Portrait Records, 1985. ↩

For instance, for the paradoxical structure of the identity of the European Union between nation-state and ‘super-state’, see Peter Pichler, ‘European Union cultural history: introducing the theory of ‘paradoxical coherence’ to start mapping a field of research’, Journal of European Integration 1 (2018), pp. 1-16. ↩

Peter Pichler, Metal Music and Sonic Knowledge in Europe: A Cultural History Since 1970, Bingley: Emerald, forthcoming. ↩