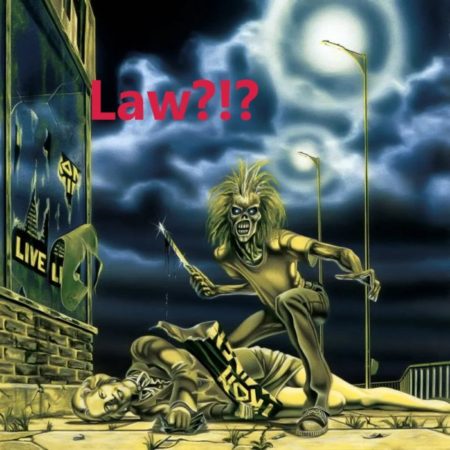

Original source: cover picture of Iron Maiden, ‘Sanctuary’, (c) EMI 1980.

Obviously, the title of this new blog post, which takes up the thoughts expressed in my recent post on our project of law-related phenomena in heavy metal culture, is not meant to be taken literally. But if we see it as a cultural-historical metaphor (very much like the above used graphic cover artwork of Iron Maiden’s Sanctuary single from 1980, where ‘Eddie’ kills Maggie Thatcher) it raises crucial research questions for our project. In this short blog post, I will attempt formulating some of these questions.

Currently, our research focuses on the early 1980s, the years of the climax of the NWOBHM. These years were the ones in that several classic metal songs were released, which centered on law in their musical material, lyrics and imagery. Just to name a few: Judas Priest’s ‘Breaking the Law’ (1980); Iron Maiden’s ‘Sanctuary’ (1980), ‘Running Free’ (1980), and ‘Prodigal Son’ (1981); and Helloween’s ‘Heavy Metal (is the Law)’ (1985). All of these songs treat law as a cultural system of norms and rules, which the metal community had to face in for this community new ways. Usually law was depicted as conservative, liberty-taking, even oppressive.

Here, the point is how the community faced it in the construction of an ‘imagined community’ in metal’s ‘golden age’. My colleague Charris Efthimiou, a musicologist, spent the past three months analyzing these classics in great detail.1 He focused on ‘law patterns’ in the songs’ lyrics and musical material. We started with these classics, because they also were a main point of reference for the initial construction of the local heavy metal scene in Graz and Styria. Charris shows very clearly that such law patterns were at the heart of the culture in those crucial years.

This finding raises serious questions. As a rule, in these songs, law is explicitly thematized and pointed out as a system of norms and ethics the emerging metal scene had to deal with. As far as we can say at this point, this rendering of law as a system of oppressive norms is clearly integrated in the emerging musical language of metal in the years 1980-85. The focus on law in the lyrics is matched in the chosen harmony progressions, guitar chords and song construction modes. Obviously, law – as a point of reference – was essential for metal in these formative years.

As most of these classics by bands like Maiden and Priest were written and performed in Great Britain in the era of ‘thatcherism’, that ideology’s approaches to the legal system and society in general (under the very conservative auspices of ‘law and order’) were necessary elements of the emerging metal discourse. Law was seen and treated as a highly conservative body of outdated and dusty traditions, even as a threatening system of oppressive rules. It seemed to take metalheads’ deserved liberties.

This narrative of law – thatcherism’s vision of law or what metal suggested it to be2 – was the crucial point of reference metal needed to develop its contrasting ethics of liberty. It was the classic ‘Other’ metal needed to construct itself. The artwork of the ‘Sanctuary’ single captures this perfectly. Thatcher’s vision of law was the ‘Other’ metal needed. To continue our research, we have to answer three crucial questions: 1) How did this narrative of law circulate in Europe? 2) How did it advance to the global metal scene? 3) And finally: How was it taken in in the regional metal scene in Graz and Styria? Put ironically, Maggie Thatcher did not make metal but she supported it with her political agenda greatly.

Edit, 10 June 2020: Engaging with my post, legal philosopher Christian Hiebaum commented that thatcherism was not only about conservative ‘law and order’ ideologies. Thatcherism also promoted individualism and individual liberty, but mainly in the economic sphere – this was key to its brand of neoliberalism. This critical remark made me dig a bit deeper into socio-historical literature on thatcherism.

In 2010, Brian Harrison published a survey book entitled Finding a Role? The United Kingdom, 1970-1990 as a part of the ‘New Oxford History of England’ series. Strikingly, Harrison described how the law reform movement in the UK in the 1980s saw the British legal tradition as elitist and oudated:

The parliamentary draughtsmen offered stiff resistance in the early 1970s (…) but during the 1980s pressurce built up for demystifying law in several ways. Its esoteric language – with its archaic forms, Latinisms, and and formulaic phrasing – was now being challenged (…) As for wigs and gowns, more people now felt that these ‘priestly garments’ unduly distanced the judges ‘from ordinary men and women’.3

What Harrison says here is about the image and narrative of law in the Thatcher era, especially in the early 1980s. Law had to be ‘demystified’. This is very much in line with my argumenation on thatcherism’s take on law. Still, the question how the neoliberal individualism inherent of this ideology affected the narrative of law is not really explained with this.

I suspect that metal culture at the apex point of the NWOBHM did focus on the conservative image of Thatcher as a public person. Her neoliberalism seemed to be outplayed by this. But we have to continue our research into this. I am also thankful for any feedback on this specific aspect.

Charalampos Efthimiou, Musicological analysis of Judas Priest’s ‘Breaking the Law’ (1980); Iron Maiden’s ‘Sanctuary’ (1980), ‘Running Free’ (1980), and ‘Prodigal Son’ (1981); Helloween’s ‘Heavy Metal (is the Law)’ (1985). Not published work. Graz, 2020. ↩

See Eric J. Evans, Thatcher and Thatcherism, London: Routledge, 2013. ↩

Brian Harrison, Finding a Role? The United Kingdom, 1970-1990, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2010. This volume was published as a part of the ‘New Oxford History of England’ series, ed. by J.M. Roberts. ↩